Executive summary

Deep – but hopefully brief – recession

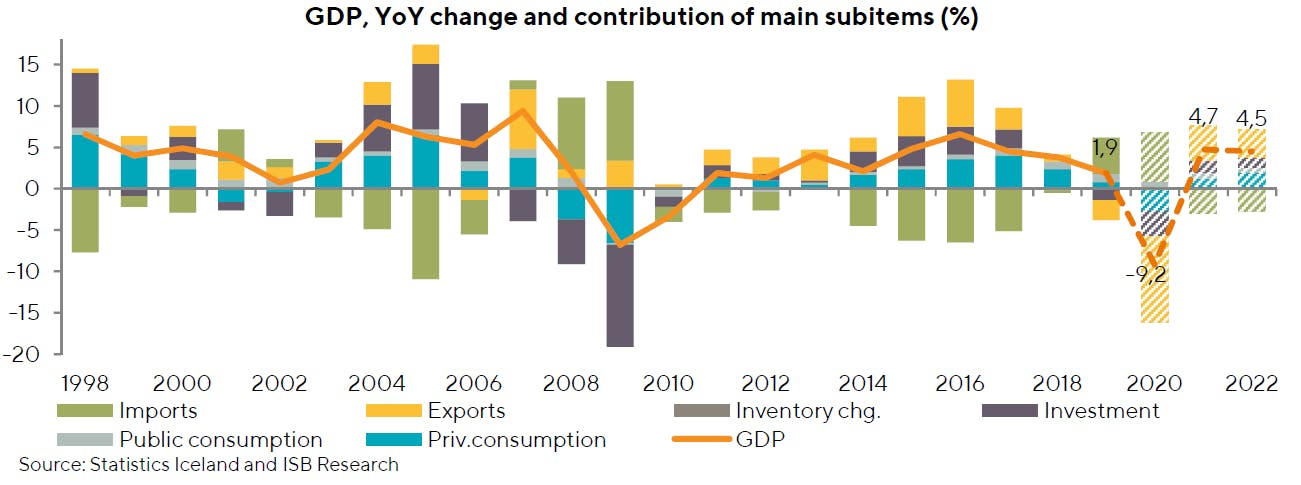

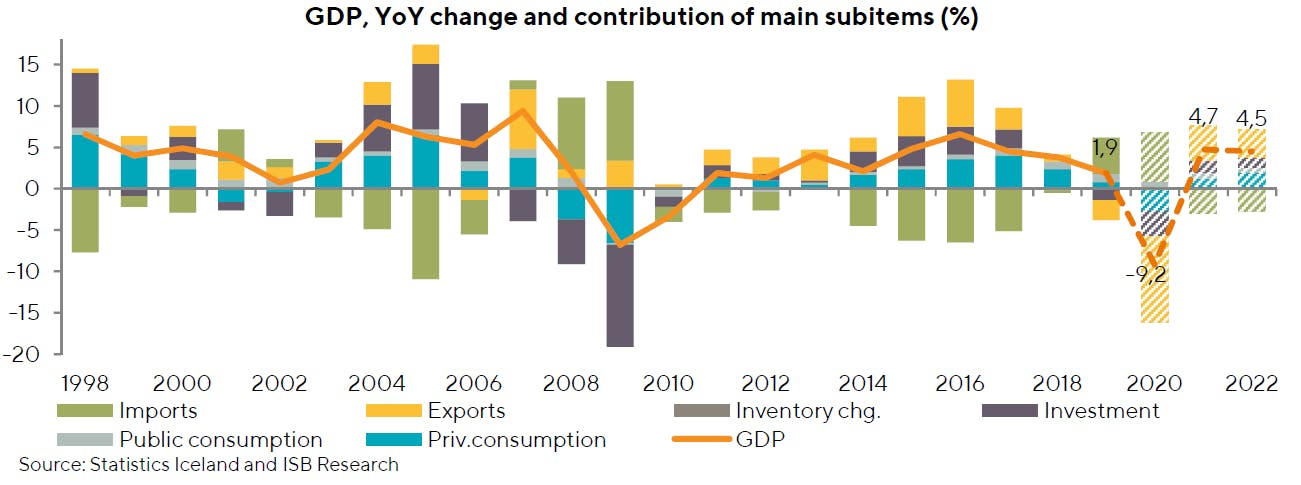

The COVID-19 pandemic has upended the short-term economic outlook. It now appears clear that the year 2020 will see a deep economic contraction, whereas Íslandsbanki Research projected GDP growth for the year at 1.4% in its January forecast. Our current forecast provides for a 9.2% contraction this year.

Tourism revenues are expected to shrink by more than half between years. Good exports will contract somewhat, owing to reduced aluminium exports and pandemic-driven difficulties with transport of frozen fish and other goods.

Private consumption will contract sharply because of a surge in unemployment, temporary restrictions on certain types of consumption, and consumer caution during a time of uncertainty.

Private investment is likely to shrink markedly. Mitigating measures by the Government will boost public investment, however.

Imports will probably contract significantly because of reduced overseas travel, a contraction in domestic demand,and the impact of the weaker ISK on internal demand for imports and domestic goods and services.

The pace of economic recovery depends on how quickly the pandemic recedes. If the pandemic is on the wane after mid-year, the outlook will be good for robust GDP growth in the latter two years of the forecast horizon.

External trade more resilient than expected

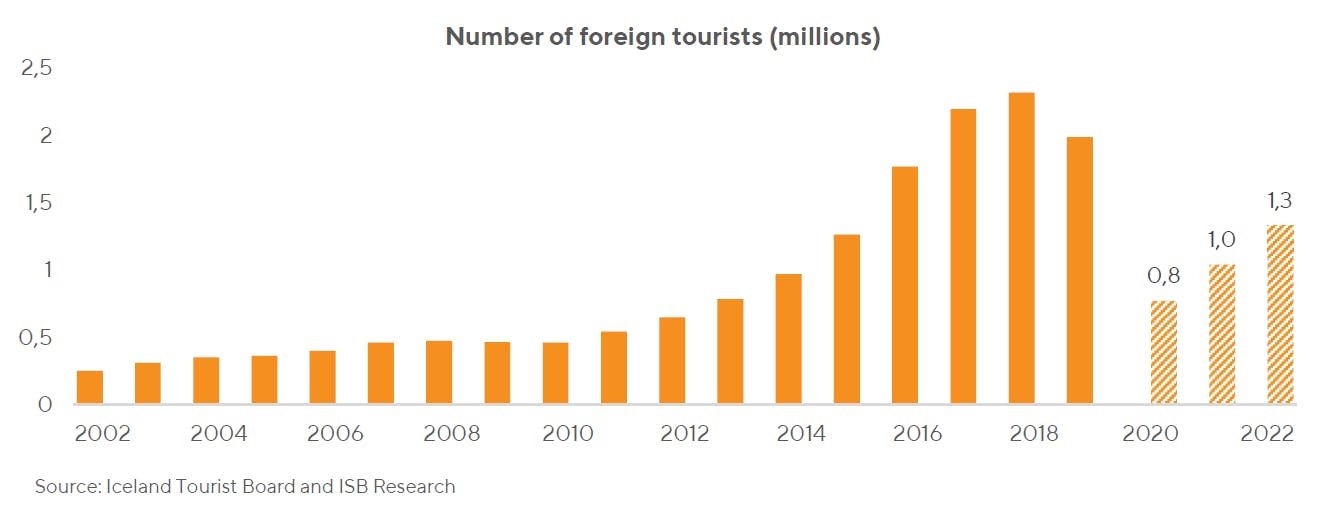

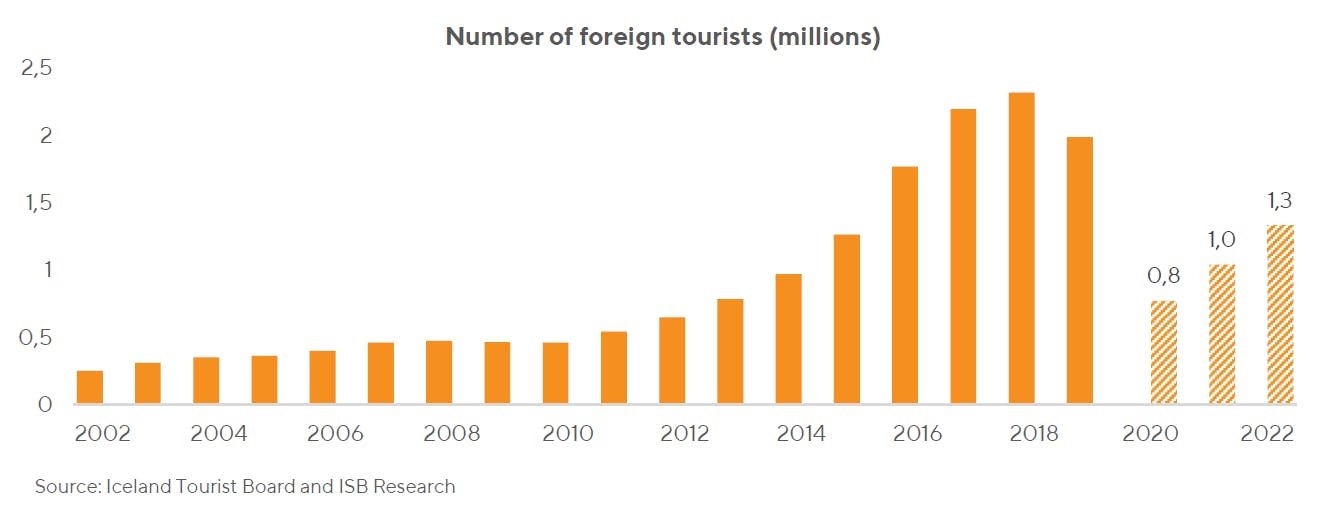

Nearly 2 million foreign tourists visited Iceland in 2019, making it the third-largest tourism year to date, despite a 14% YoY decline.

The current situation is entirely different, of course, and it is clear that tourism will be hit hard in the near term, both by the virus and by the travel restrictions imposed in response to it. It is highly uncertain when countries will open their borders and when people will be willing to risk travelling again.

Tourism is Iceland’s largest economic sector, generating the equivalent of nearly four out of every ten ISK in foreign revenues. Revenues from foreign tourists totalled ISK 470bn in 2019. Over the same period, the fishing industry generated revenues of ISK 260bn and aluminium exports ISK 212bn. Tourism revenues will foreseeably decline by more than half year-on-year in 2020, dealing a heavy blow to the broader economy.

We expect tourist visits to resume in the autumn, with total arrivals for the year projected at around 750,000, about the same as in 2013. We therefore estimate the YoY contraction in tourist numbers at roughly 62%. In the first three months of 2020, roughly 330,000 tourists visited the country.

We expect a slow and gradual recovery starting in 2021, with just over 1 million arrivals, followed by 1.3 million in 2022.

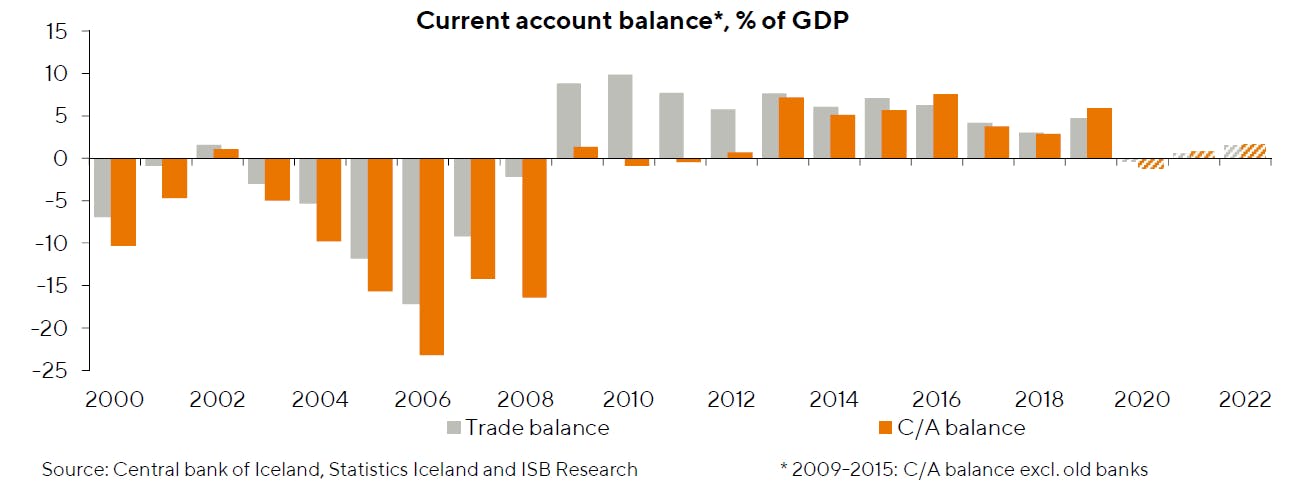

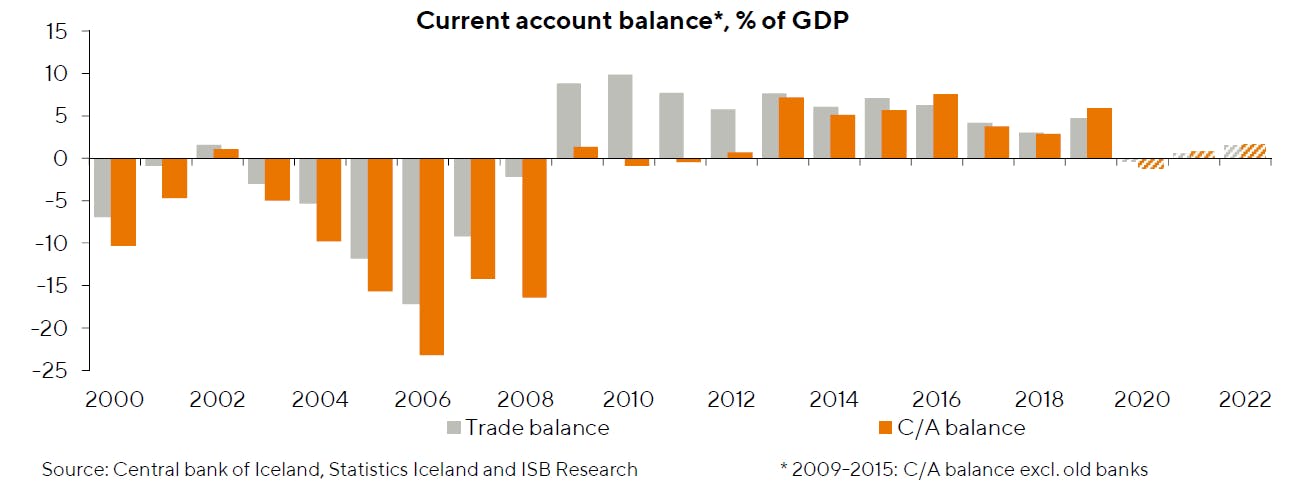

The balance on combined goods and services trade showed a sizeable surplus in 2019, despite reduced tourist numbers and the failure of the capelin catch. The deficit on goods trade totalled ISK 99bn, while services trade generated a surplus of ISK 239bn for the year.

Actually, last year’s goods account deficit was the smallest since 2015. This is due mainly to the sharp contraction in imports, although exports did develop more favourably than had been anticipated. By the same token, the contraction in services exports was smaller and the contraction in imports larger than expected.

Needless to say, this year will be far less favourable. The surplus on services trade will be more or less wiped out by the collapse of tourism revenues, but on the other hand, the goods account deficit looks set to be much smaller, owing to a sizeable contraction in imports of consumer goods and investment goods. Our forecast assumes that exports will rebound next year, provided that tourism firms up. If our projections materialise, the surplus should grow gradually, even though imports will also grow as demand takes hold once again.

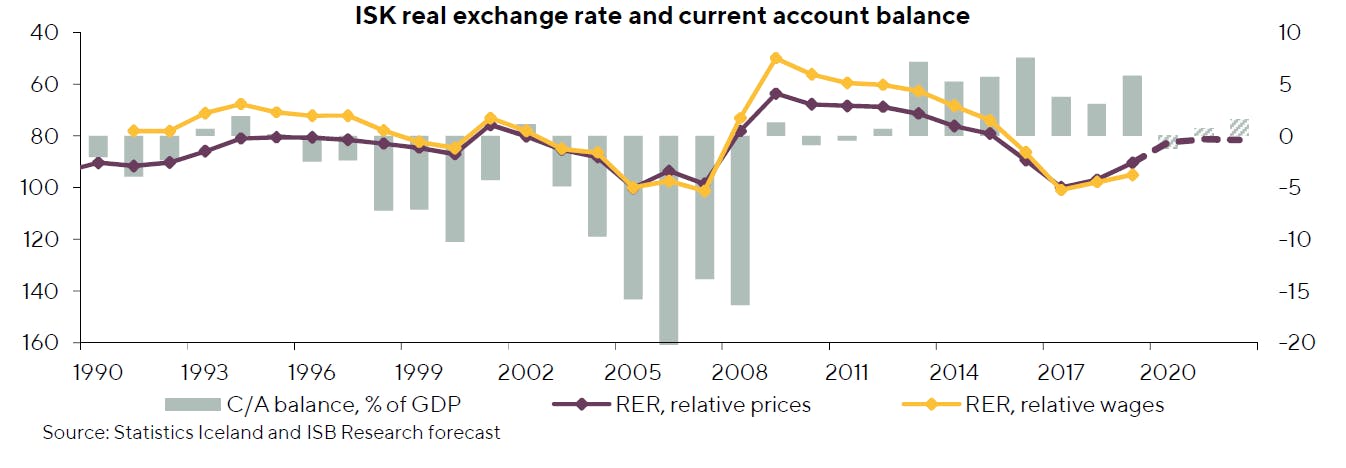

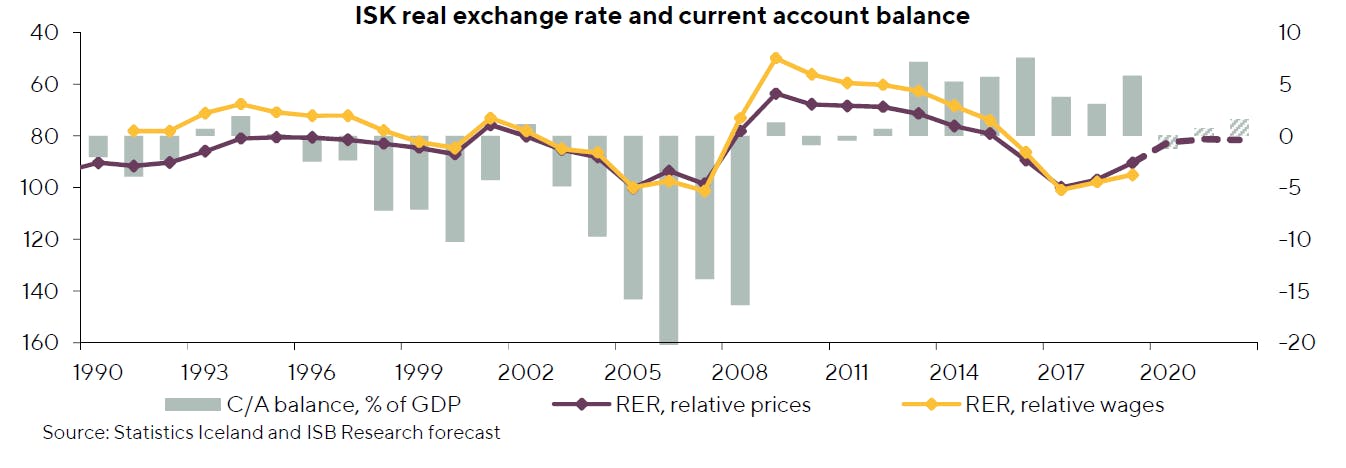

After the longest continuous current account surplus in the history of the Republic (2012-2019), the outlook is for a deficit this year.

According to our forecast, the balance on goods and services trade will probably be slightly negative, as lost tourism revenues will outweigh the improvement in goods trade. Furthermore, the outlook is for the balance on primary and secondary income to show a deficit, as equity securities constitute a large share of Iceland’s external assets and will presumably generate less investment income this year.

On the other hand, the outlook for the current account balance is reasonably good further ahead. A lower real exchange rate will promote a shift in demand into the domestic economy, and services revenues could grow strongly in coming years. In addition, Iceland’s international investment position (IIP) is still healthy; thus it is quite likely that the balance on primary and secondary income will make a positive contribution to the current account balance.

We forecast this year’s current account deficit at 1.2% of GDP, followed by surpluses of 0.7% and 1.6% in 2021 and 2022, respectively. In our opinion, the current economic crisis will not obliterate the improvements made in Iceland’s external balance in the wake of the 2008-2009 crisis.

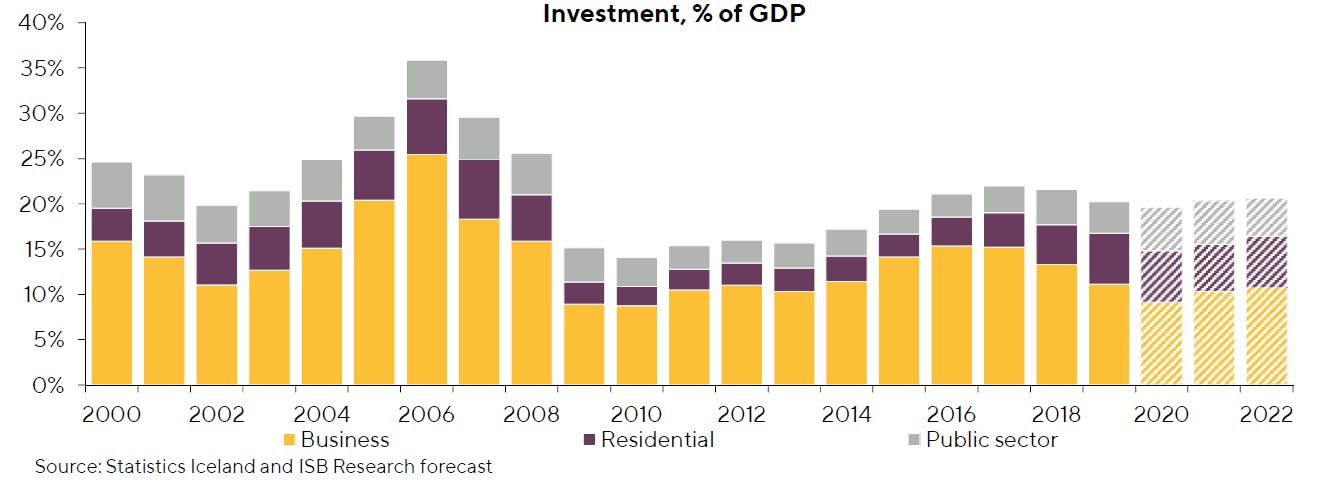

Investment softens considerably

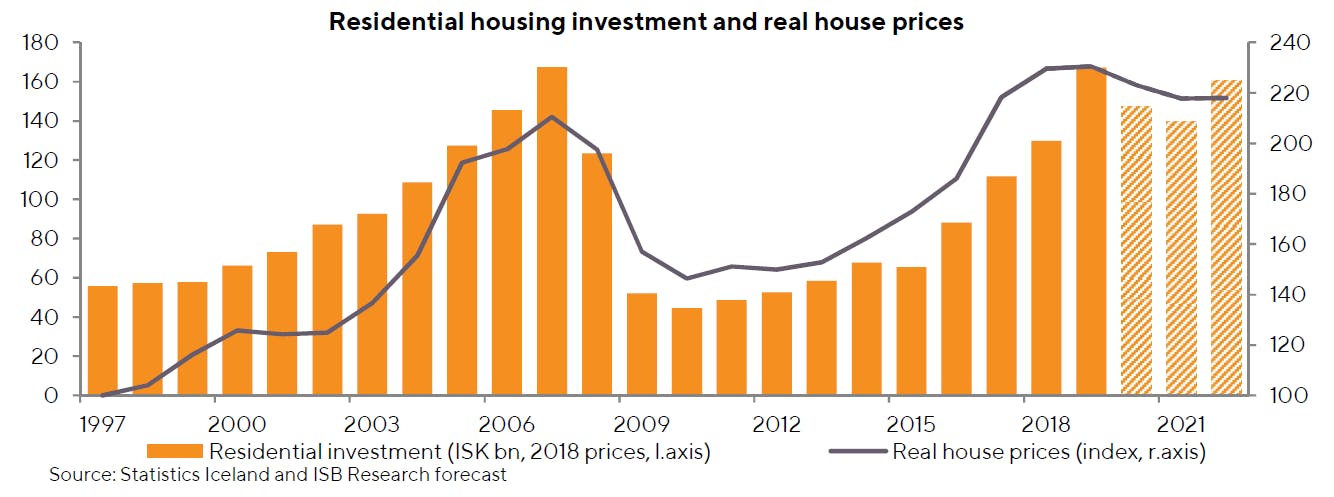

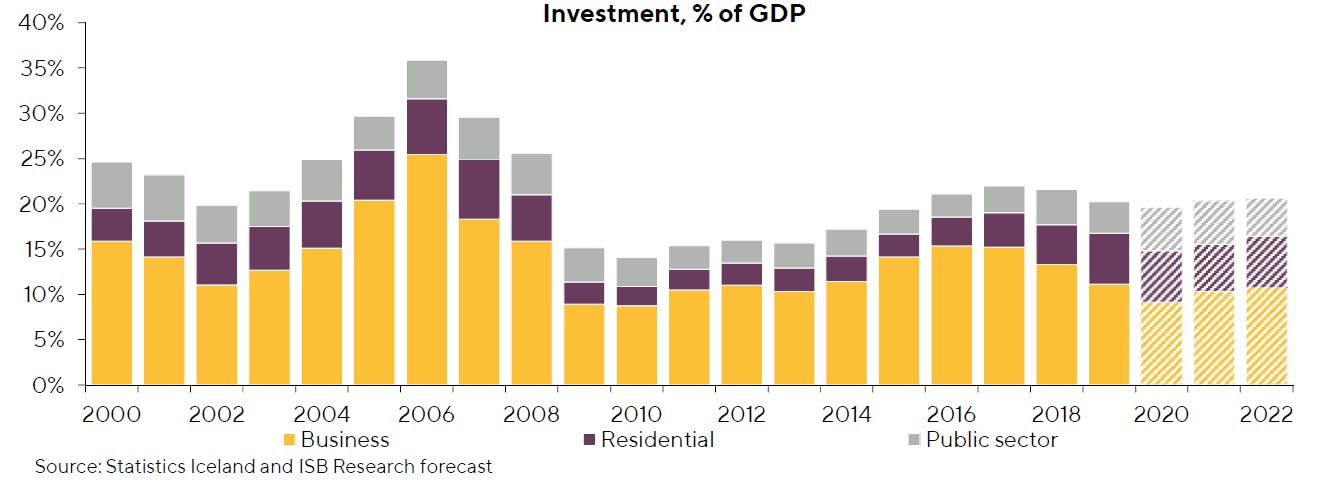

Investment contracted in 2019, for the second year in a row. Residential investment retained its momentum, however, although it was outweighed by the contraction in business investment and public investment. Total investment declined by 6.3% YoY in 2019.

The outlook is for a sizeable contraction in investment this year as well. The main factor in the downturn is a 28% contraction in business investment, although we also expect residential investment to decline by 12% YoY. On the other hand, public investment should be quite strong, owing to Government measures designed to mitigate the economic impact of the COVID-19 shock. We project growth in public investment at roughly 23% this year.

In 2021 and 2022, business investment will continue to be the main driver of investment growth. On the other hand, we expect a contraction in residential investment in 2021, followed by a contraction in public investment in 2022. In all, we forecast investment growth at 7.8% in 2021 and 6.6% in 2022.

The investment-to-GDP ratio will be just under one-fifth this year and then begin to rise again in the years to follow. Nevertheless, we expect the investment level to be below the average of the past few decades, as it is difficult to see where there might be scope for development anywhere close that undertaken in the export sector since the mid-twentieth century.

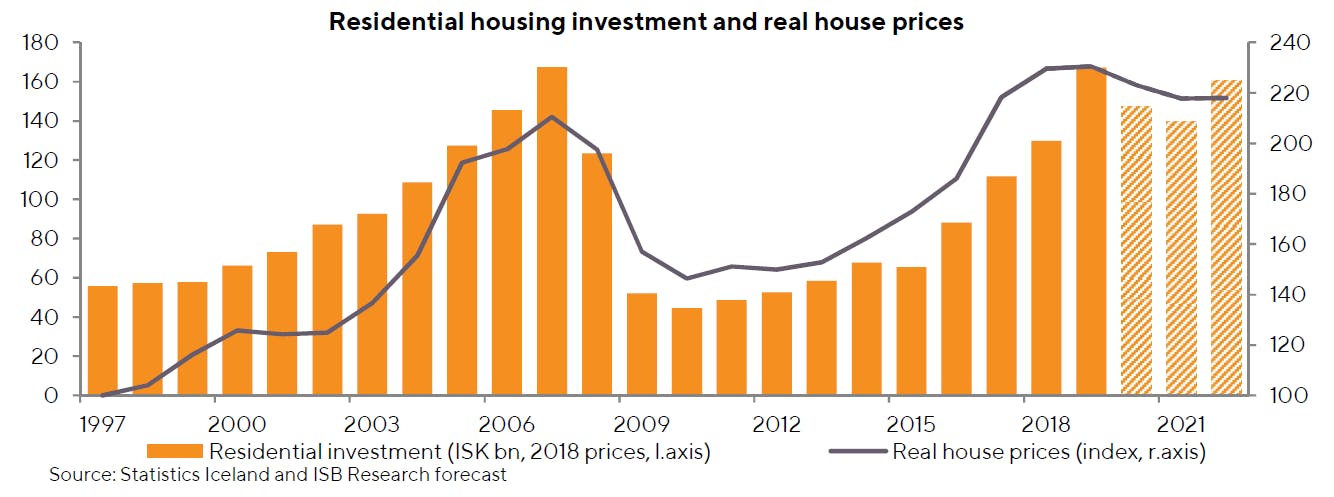

The housing market has calmed down after several turbulent years. In 2019, real house prices rose 0.4% YoY, the smallest real increase since 2012.

Since then, soaring residential investment and declining demand have combined to ease pressures in the market, and developments in real house prices and real wages have realigned after having diverged in recent years. Residential investment has surged in the past four years, growing by over 30% in 2019 alone.

We expect a contraction of 12% this year, followed by an additional 5% contraction in 2021. The Federation of Icelandic Industries’ tally of flats under construction indicates that a contraction in new construction lies ahead, and the cloudy economic outlook suggests that demand will weaken as well. We expect growth to resume in 2022, measuring 15% for that year.

Because of the worsening economic outlook, with soaring unemployment, sluggish real wage growth, and a slowdown in population growth, we expect real house prices to fall. The factor that will go furthest in supporting the demand side is favourable financing terms, as mortgage lending rates are at an all-time low.

We expect real house prices to fall by 3.2% and 2.4% in 2020 and 2021, respectively, and then remain unchanged in 2022.

Short-term labour market outlook darkens

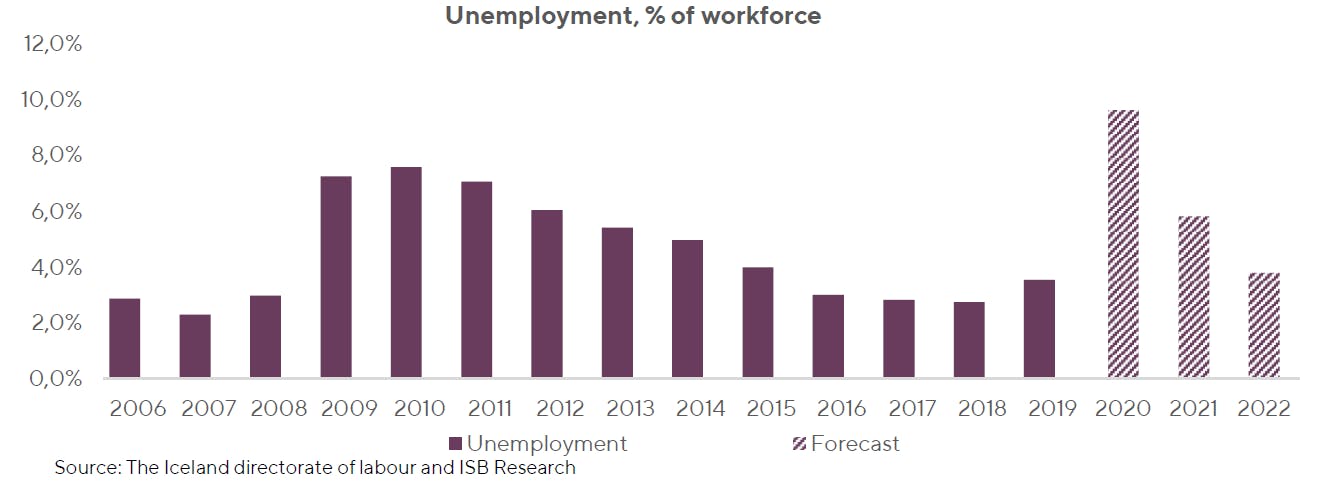

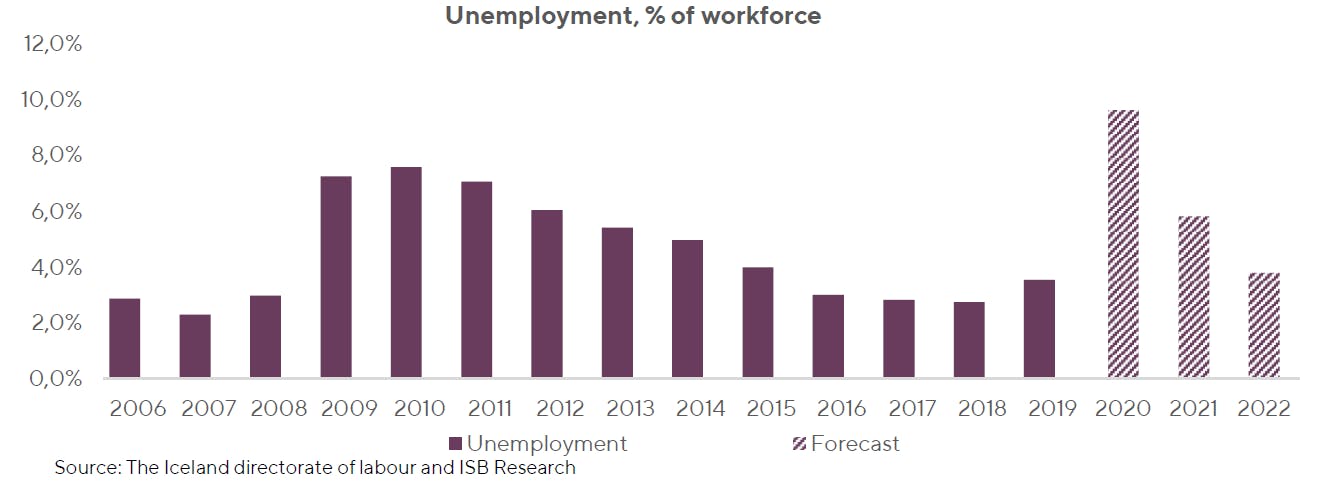

Unemployment in Iceland has averaged 3% over the past four years, which is considered very low in international comparison. This March, however, the labour market was flattened by the COVID-19 pandemic, and unemployment shot up to 5.7% during the month.

Because of the pandemic, it is plain that unemployment will be very high this year. A number of mass layoffs have already been announced, including Icelandair’s termination of some 2,000 employees, or 1% of the country’s workforce. A large number of companies have taken advantage of the part-time option offered by the Government, which allows firms to reduce employees’ job percentage rather than laying them off. Under the programme, workers who cut their hours can receive part-time unemployment benefits to top up their reduced wage income.

We expect unemployment peak at 13% at mid-year and taper off thereafter. For 2020 as a whole, we expect it to average 9.6%. The short-term labour market outlook is certainly poor, but in comparison, unemployment rose to a post-crisis high of 7.6% in 2010. All that said, we believe the current crisis will be brief. We expect unemployment to measure 5.8% in 2021 and then return to pre-pandemic levels in 2022, measuring around 3.8%.

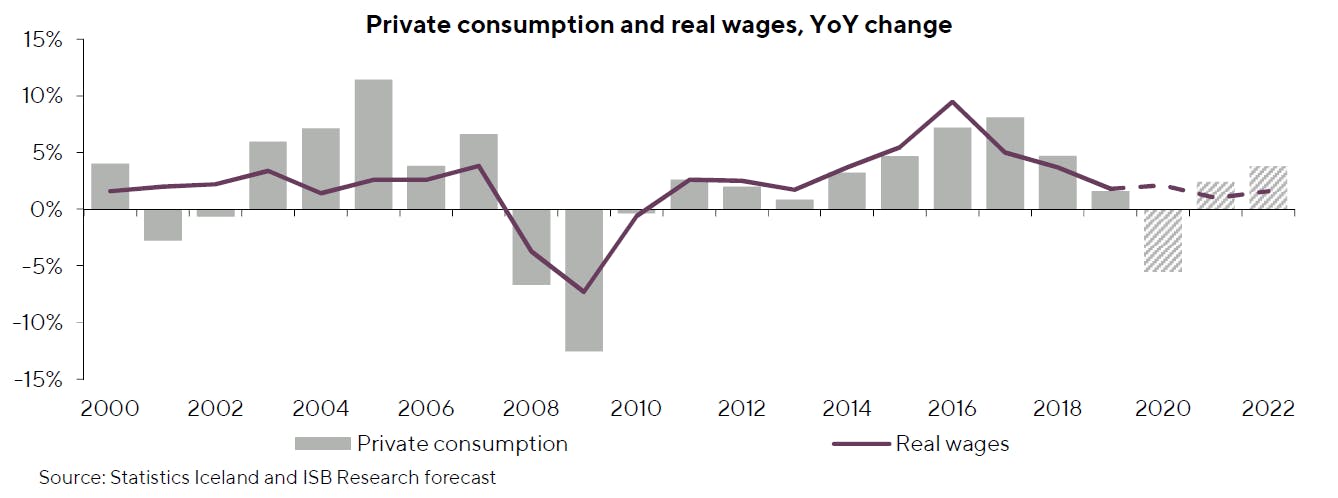

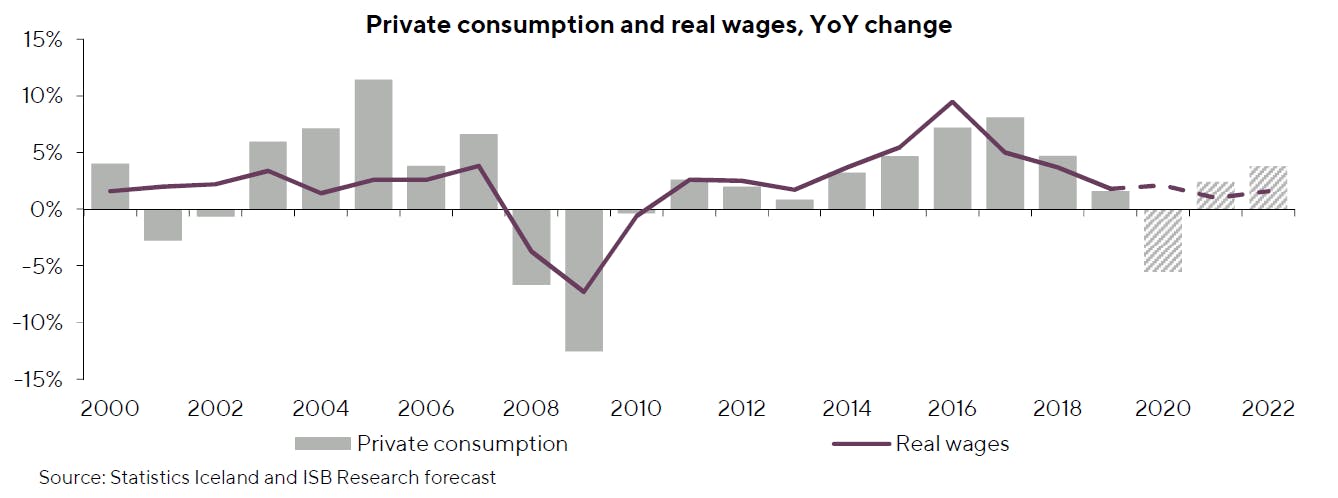

Private consumption will clearly take a hit in the quarters to come, as can be seen not only in the spike in unemployment, but also in consumer sentiment and payment card turnover figures, which paint the bleakest picture of private consumption in nearly a decade.

Restrictions on travel and gatherings will have a profound impact on consumption in the next several months, and signs of what lies ahead can already be seen in key indicators such as the Consumer Confidence Index, card turnover figures, and unemployment.

Consumption is generally sensitive to uncertainty, and some subcomponents of consumption are more likely to suffer than others. Those that are most likely to take a hit accounted for nearly 50% of all private consumption in 2019, including hotel and restaurant services and travel and transport.

Private consumption is an important factor in Iceland’s GDP growth, accounting for about half of GDP in recent years. It will inevitably be hit hard by COVID-19, and we expect it to contract by 5.5% in 2020 as a whole. We expect the downturn to be brief, however, and project that private consumption will resume next year, measuring 2.4% in 2021 and 3.8% in 2022.

Fortunately, households are in a much stronger position now than during the last crisis. Overall, households have kept their debt levels moderate and have stepped up their saving. As a result, they are less at risk of severe financial distress than they would be otherwise, even in the face of a temporary dip in income.

ISK weakens, following the typical pattern in a contraction

The ISK has depreciated by nearly 14% against major currencies since the turn of the year.

The depreciation took place mostly in March and April, after a fairly stable two months at the beginning of the year. The Central Bank (CBI) has intervened in the foreign exchange market to slow down the slide in the exchange rate and prevent short-term spiral formation. The CBI sold just over EUR 100m from its international reserves in March and April, but it still has about EUR 6bn on hand.

Developments year-to-date are reminiscent of other depreciation episodes in recent years. With the exception of 2008, when the foreign exchange market collapsed, the pattern appears to be that when the ISK depreciates, it finds a new temporary equilibrium roughly 10-15% below the previous level.

The real exchange rate of the ISK has fallen by nearly one-fifth from its peak at the height of the tourism boom three years ago. As a result, Iceland is now much more competitive internationally than it was a few quarters ago. By this measure, Iceland is about as expensive a destination as it was in H1/2016.

We do not consider it a given that a lower real exchange rate is needed to maintain balanced external trade further ahead. In fact, it could be argued that some rebound could be accommodated in the future.

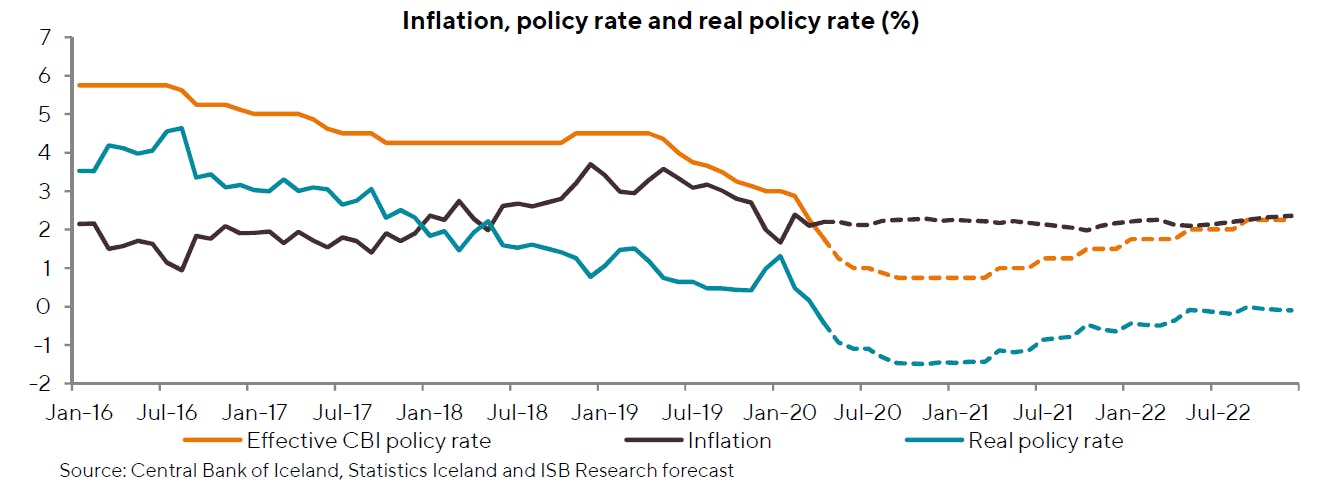

Inflation relatively stable; lower policy rate ahead

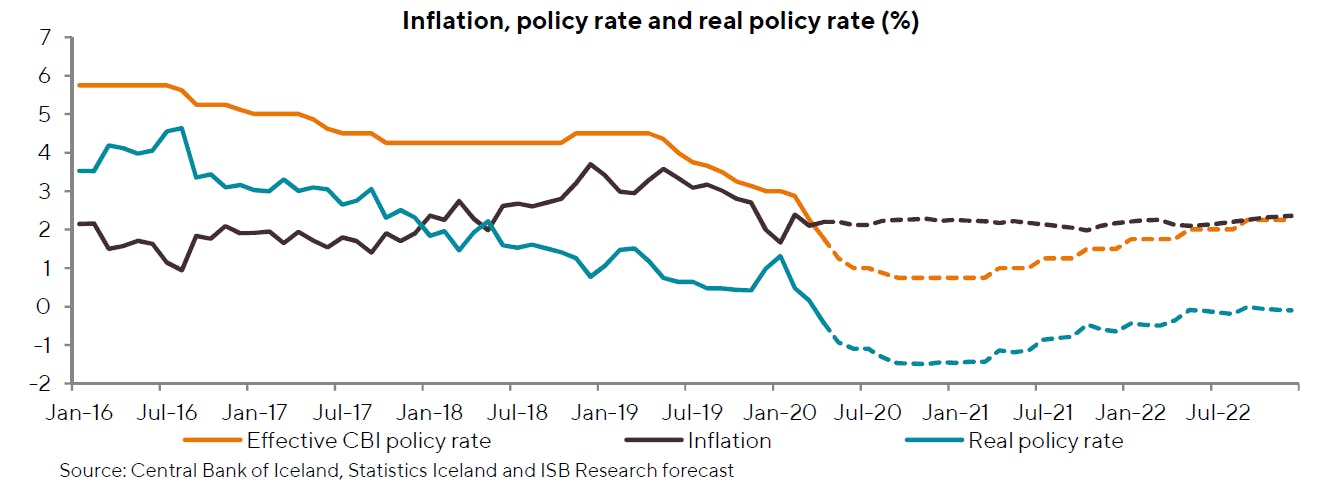

As is mentioned above, the ISK has weakened significantly year-to-date. Other things being equal, this would generally trigger an uptick in inflation. This time around, however, inflation has hardly budged, measuring 2.2% in April. We expect it to remain below the CBI’s inflation target in the coming term.

The reason inflation has not taken off is that various other forces have kept it under wraps. Oil prices have plummeted, house price inflation has lost momentum, and the decline in demand has reduced inflationary pressures.

The outlook is for modest inflation in the near future. We expect inflation to remain below the CBI’s inflation target through the end of the forecast horizon, averaging 2.2% this year and 2.1% in 2021, and then inching upwards to an average of 2.3% in 2022.

The inflation outlook is highly uncertain, however, and the ISK is one of the key factors in that uncertainty. Our forecast is based on the assumption that the ISK will remain broadly stable at close to the current level. On the other hand, both house prices and weak domestic demand could curb inflation even more.

The CBI’s policy rate has been lowered by 1.25 percentage points in 2020 to date. The key interest rate is now at an all-time low of 1.75%. Over this same period, the CBI has eased liquidity requirements, scaled down the banks’ capital requirements, and expanded the list of securities eligible as collateral for credit facilities.

We anticipate a further decline in interest rates and expect the key rate to be 0.75% before the end of Q3/2020. Thereafter, we expect it to remain steady at 0.75% through 2020 and then begin rising again in 2021 as the economic outlook improves. Interest rates will nevertheless be low in historical context for the remainder of the forecast horizon.

Long-term nominal interest rates are currently about 2.4% and long-term real rates 0.3%. We expect average long-term nominal rates to be lower this year than at any time since they were liberalised over 30 years ago. Both nominal and real rates will rise slightly in the latter half of the forecast horizon.

We forecast that long-term nominal rates will be around 3.0%, and real rates close to 0.8%, by the end of the forecast horizon. According to this, the long-term breakeven inflation rate will be around 2.2% as 2022 progresses. It is currently about 2.1%, after falling steeply in the recent past.

Economic policy response mitigates the shock, and foundations are strong

The Government has already rolled out three packages of measures to offset the economic impact of COVID-19. The combined scope of these packages comes to approximately ISK 330bn (11% of GDP), but the direct impact on Treasury operations in 2020 will probably be less, or around 6-7% of GDP.

The measures taken by the Icelandic authorities are similar to those introduced in other advanced economies. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated in April that G20 countries’ rescue packages averaged 3.5% of the respective countries’ GDP. Indirect measures adopted by the same countries, such as credit facilities and State loan guarantees, total many times that amount, however.

It could be argued that the Icelandic authorities should be more willing than their counterparts abroad to beef up their rescue packages if the situation deteriorates further. Iceland’s public debt is low compared to other countries. The outlook is for total public debt to rise to about 40-45% of GDP after accounting for the measures mentioned above, whereas the IMF estimates that the debt-to-GDP ratio for the G20 countries will probably average 132% by the year-end. Furthermore, because Iceland’s tourism industry accounts for a large share of the country’s export revenues and labour market activity, it is more important to keep the sector healthy.

Fortunately, many of the pillars of the Icelandic economy were quite strong when COVID-19 struck.

Substantial deleveraging by households, firms, and the public sector in the past decade has shored up financial resilience. This reduces the risk that temporary headwinds will trigger serious default and insolvency in the private sector, and it enhances the Government’s countercyclical capacity.

The financial system has been transformed and is now characterised by prudence and effective supervision. This, plus moderate private sector debt, reduces the likelihood of financial crises and procyclical aftereffects from lending activity.

Iceland’s positive NIIP and moderate external debt, combined with the CBI’s ample international reserves, greatly reduce the risk of capital flight and the associated negative effects on the exchange rate, inflation, and purchasing power.

The Icelandic job market is unusually flexible in international comparison, labour participation is high, and unemployment is lower than in most advanced economies.

Unlike many neighbouring countries, we have been fortunate enough to amass large pension funds. This reduces the risk that an aging population will turn out to be a drag on the public sector and an undue burden on future taxpayers.